About the Program

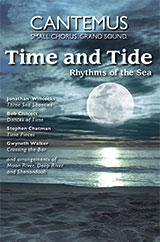

Time and Tide: Rhythms of the Sea

Apri 28 & 29 and May 6, 2018 | Download PDF

Nae man can tether time or tide

(Robert Burns, Tam o' Shanter)

Unfathomable Sea

whose waves are years,

Ocean of Time, whose waters of deep woe

Are brackish with the salt of human tears!

Thou shoreless flood, which in thy ebb and flow

Claspest the limits of mortality!

(Percy Bysshe Shelley, Time)

Today’s concert, Time and Tide, represents a plain and straightforward interpretation of a very complicated proverb. Who knew that this little expression could be so shrouded in linguistic and historical mystery? In its most popular use, we often hear the expression, “Time and tide wait for no man.” But how did this little saying come to be? It is often attributed to some of literature’s greatest heroes: Chaucer, Southwell, Shakespeare, Burns, to name a few.

Most often, the expression is linked to a 12th-century telling (Henry Huntingdon) of an 11th-century myth: King Canute and the Tide. In the story, Canute demonstrates to his flattering courtiers that he has no control over the elements, failing to make the sea obey his command and explaining that secular power is vain compared to the supreme power of God. The episode is frequently alluded to in contexts where the futility of “trying to stop the tide” of an inexorable event is pointed out. This literal interpretation of “tide” is what is now often assumed. However, “tide” did not refer to the contemporary meaning of the word, that is, the rising and falling of the sea, but to a period of time or a season.

So, today, you will hear a collection of pieces that represent both the tides of the ocean and the tides of time. I have crafted a program that refers to water, rivers, seas, moons, clocks, seasons, pastimes -- a platform for some of spring’s most beautiful and powerful music.

Randall Thompson’s “Two Worlds” is a gentle meditation on old age, on the light that shines “through chinks that time hath made.” Bob Chilcott’s Dances of Time give us contrasting pieces that dance us through various aspects of time – representing writers and texts as diverse as King Henry VIII, Ecclesiastes and Sara Teasdale. Gwyneth Walker’s “Crossing the Bar” liltingly sets Tennyson’s placid and accepting attitude toward mortality. The poet uses the metaphor of a sand bar to describe the liminal barrier between life and death.

Stephen Chatman’s Time Pieces consists of settings of texts or sounds relating to the idea of time. Both the music and the diverse secular texts echo various styles, aesthetics, and emotions, chronologically spanning many centuries. The contrapuntal, spiritual, and dramatic qualities of “Tempus” contrast the light-hearted, bittersweet tone of “Come, My Celia,” composed in a quasi-Renaissance style. The culminating “Clocks” is inspired by the composer’s antique grandfather clock. It is a textual and musical glossary of clock sounds, consisting of repetitive “tick-tock” motives and the occasional “cuckoo” or low, loud Westminster chime sounds.

Liberal use of the word “shanty” by folklorists of the 20th century has expanded the term’s conceptual scope to include “sea-related work songs” in general. However, the shanty genre is distinct among the various global work song phenomena. The shanty was sung to accompany certain work tasks aboard sailing ships, especially those that required a bright walking pace. It is believed to have originated in the early 19th century, during a period when ships’ crews, especially those of military vessels, were large enough to permit hauling a rope while simply marching along the deck. “Drunken Sailor,” also known as “What Shall We Do with a/the Drunken Sailor?” is perhaps the most mainstream and popular of this body of songs. Each successive verse suggests a method of sobering or punishing the drunken sailor. “Enticement” (an aggressive drinking song) and “Demons” (a serious lament) round out the trio of shanties.

“Away from the Roll of the Sea” is one of Canada’s most endearing folksongs, cherished for soaring melody and a deep connection to treasured Canadian waterways. Dan Forrest’s “Who Can Sail without the Wind?” is a poignant Swedish folksong that became popular among Scandinavian immigrants in the American upper Midwest. “Shenandoah” is a favorite piece in the Cantemus repertoire, and it is my pleasure to bring the piece to life with this lovely group. And for pure heart and good measure, we have included “Moon River” and “Deep River” – one popular, one spiritual – both beloved.

In the end, I hope that this little proverb has properly set the stage for some glorious music. We rest here on the North Shore, surrounded by the wild beauty of the tides, a roaring and commanding sea. The history of vocal music is rich with images of the seas, rivers, inlets, and tides, reminders of our natural inheritance, and it is our pleasure to swim in the diverse waters of motet, madrigal, shanty, folksong and spiritual. As always, I look forward to seeing you at the reception and thank you for your continued support of Cantemus Chamber Chorus.

—Jane Ring Frank, Artistic Director